By the end of the 12th century, the authority of the Japanese central government had declined. Bands of warriors grouped together for protection forming local aristocracies. Feudalism had come of age, and was to dominate Japan for several centuries. With the establishment of the Shogun in Kamakura and military rule controlling Japan, a new military class and their lifestyle called Bushido, "the way of the warrior," gained prominence. Bushido stressed the virtues of bravery, loyalty, honor, self discipline and stoical acceptance of death. Certainly, the influence of Bushido extended to modern Japanese society and Kendo was also to be greatly influenced by this thinking.

The Japanese warrior had no contempt for learning or the arts. Although Kenjutsu, "the art of swordsmanship," had been recorded since the 8th century, it gained new prominence and took on religious and cultural aspects as well. Sword making became a revered art. Zen and other sects of Buddhism developed and the samurai often devoted time to fine calligraphy or poetry.

The next great advance in the martial arts occurred during the late Muromachi period (1336-1568) often call the "age of Warring Provinces" because of the many internal conflicts. This period brought an increased demand and respect for men trained in the martial arts. Consequently, many schools of Kenjutsu arose, eventually numbering about 200. Each was taught by a famous swordsman whose techniques earned him honor in battle. Real blades or hardwood swords without protective equipment were used in training resulting in many injuries. These schools continued to flourish through the Tokugawa period (1600-1868), with the Ittoryu or "one sword school," having the greatest influence on modern Kendo.

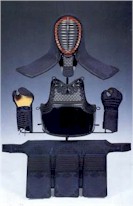

Kendo began to take its modern appearance during the late 18th century with the introduction of protective equipment: the men, kote and do and the use of the bamboo sword, the shinai. The use of the shinai and protective armor made possible the full delivery of blows without injury. This forced the establishment of new regulations and practice formats which set the foundation of modern Kendo.

With the Meiji Restoration (1868) and Japan's entry into the modern world, Kendo suffered a great decline. The Samurai class was abolished and the wearing of swords in public outlawed. This decline was only temporary, however, interest in Kendo was revived first in 1887 when uprisings against the government showed the need for the training of police officers. Later the Sino-Japanese War (1894-95) and the Russo-Japanese War (1904-05) again encouraged an awareness of the martial spirit.

Consequently in 1895, the Butokukai, an organization devoted to the martial arts was established. In 1911, Kendo was officially introduced into the physical education curriculum of middle schools and in 1912, the Nihon Kendo Kata, a set of regulations for Kendo, was published. In 1939 as Japan prepared for war, Kendo became a required course for all boys.

After Would War II, because of its nationalistic and militaristic associations, Kendo was outlawed and the Butokukai was disbanded. However by 1952, supporters of Kendo successfully reintroduced a "pure sport" form of Kendo, called Shinai Kyogi which excluded the militaristic attitudes and some of the rougher aspects of practice characteristic of prewar Kendo, into the public schools. Today, Kendo continues to grow under the auspices of the All Japan Kendo Federation, the International Kendo Federation, and federations all over the world.

Although the outward appearance and some of the ideals have changed with the changing needs of the people, Kendo continues to build character, self-discipline and respect. Despite a sportlike atmosphere, Kendo remains steeped in tradition which must never be forgotten. For here lies the strength of Kendo which has carried it throughout history and will carry it far into the future.

|

Kendo equipment consists of the swords, uniform and armor. There are two types of wooden swords used. First, the bokken or bokuto, a solid wood sword made of oak or another suitable hardwood. The bokken is used for basics and forms practice (kata). Second, the shinai, is made up of four bamboo staves and leather. The shinai is used for full contact sparring practice. The uniform or dogi consists of woven cotton top called a keikogi and pleated skirt-like trousers called a hakama. The armor or bogu consists of four pieces: the helmet (men), the body protector (do), the gloves (kote), and the hip and groin protector (tare). Modern Kendo armor design is fashioned after the Oyoroi of the Samurai.

|

|

A Kendo practice is composed of many types of training. Each type has a different purpose for developing the Kendo student.

Kendo, like other martial arts requires discipline and a dedication to training. A new student begins with learning the basics such as: etiquette (reigi), different postures and footwork, and how to properly swing a sword. The student progresses through a series of skills preparing them to begin training with armor (bogu).

Once a student begins to practice in armor, a practice may be composed of any or all of the following types of practice and this will depend upon what the instructor's focus is at a particular time:

- Kiri-Kaeshi: successively striking the left and right

men, practice centering, distance, and proper cutting while building

spirit and stamina.

- Waza-Geiko: technique practice in which the student learns to use the many techniques of Kendo with a receiving partner.

- Kakari-Geiko: short, intense, attack practice which teaches continuous

alertness, the ability to attack no matter what has come before, as

well as building spirit and stamina.

- Ji-Geiko: sparring practice where the kendoist has a

chance to try all that he or she has learned with a resisting partner.

- Gokaku-Geiko: sparring practice between two kendoist of similar skill level.

- Hikitate-Geiko: sparring practice where a senior kendoist guides a junior kendoist through practice.

- Shiai-Geiko: competition matches which are judged on the

basis of a person scoring valid cuts against an opponent.

Almost all martial arts have a set of kata. Kendo is no exception.

Kata are pre-set sequences of motions which illustrate very deeply one

or more aspects of the art. Repetitive practice of kata internalizes

the lessons of the kata.

Kendo kata are practiced with a solid wooden sword called a bokken. There are ten kendo kata specified by the All Japan Kendo Federation. Each kata studies a single set of concepts in a very pure setting allowing the practitioner

to delve deeply into these concepts.

Kendo kata are practiced between two people, the Uchitachi and the Shidachi. In kendo kata, the Uchitachi attacks the Shidachi who in turn demonstrates a proper response to the attack. Seven of these kata are illustrations of the technique of the long sword against

the long sword. The last three kata illustrate the short sword

defending against attacks by the long sword.

Prior to the invention of the shinai and bogu, kata were the only way

that kendoists could safely practice. Originally, the role of Uchitachi was taken by the

teacher and the role of Shidachi by the student. This tradition carries over into modern

Kendo kata in that the Uchitachi always sets the pace and distance at

which the actions are performed.

No attempt will be made here to present the philosophy of Kendo. Each Dojo will have similar but sightly different ideas of what Kendo should be. The student must discover through their Dojo and themselves what this is. The All Japan Kendo Federation Kendo has presented a Meaning of Kendo.

Copyright © 2002 www.kendo-usa.org

Site Disclaimer: This website is posted for informational purposes only about Kendo in the United States. Information on this website is posted from many different sources and every effort is made to post accurate information. The study of Kendo must be done under the supervision of a qualified instructor and with proper equipment. Failure to do so could result in serious injury or death. Errors may occur and users use this site without warranties of any sort implied and at their own risk.